After writing comes possibly the most crucial stage of all. Thumbnailing takes the script I’ve written and turns it into a very rough draft of what the entire book will be.

I start off with the script infront of me, working through it page-by-page to establish how the pages will lay out in the book. Unlike a prose book, where text flows from page to page without any thought by the author, comics are paced panel-to-panel and page-to-page.

What this means is that while in prose a sentence may be split across a page-turn without any effect on the reader, in comics the page-turn is a significant part of the reader’s experience. In comics, page-turns are often used to help signify a change of scene or time, and most artists attempt to hold back any shocking visual reveals until after a page turn. There’s no tension in looking at a character on a left hand page when in the corner of your eye you can see them getting eaten by monsters on the right hand page.

In the case of my non-ficiton work, I try and pace pages so that each page spread covers one topic, and so that any page turn moves us on to the next part of the argument.

Of course, the scripts I’ve written don’t always play along with this idea. It’s my work at the thumbnailing stage to break down the script so that the pace of things is satisfying, and so that pages that belong on the same page-spread end up together.

Sometimes that means adding in big splash pages, while others it means splitting a page in two. Fortunately in this case, I rarely had to meddle too much – sometimes simply starting the chapter on a left or right hand page was enough to establish the right pacing so that every page ended up facing its natural mate.

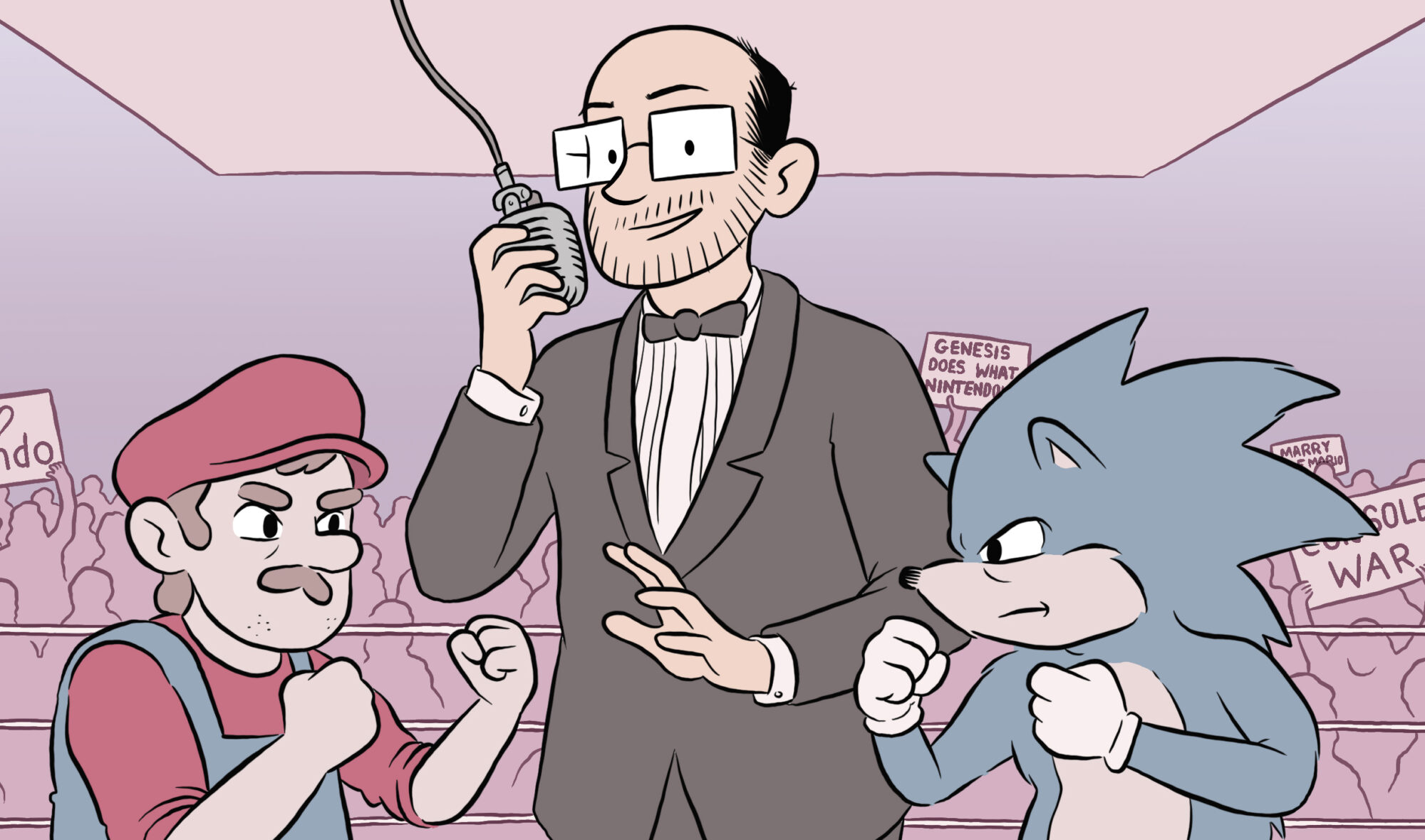

From here I began work on actually visualising the book. In a sketchbook I would measure out small versions of the page spreads. Then begins a visualisation process, involving further research into the time-period, locations and people I’ll later be drawing. It’s a fun process, and with this project it was great getting to research a number of iconic 20th century eras for fashion and decor ideas, as well as all the evolving technologies of the era.

It’s not just the visual content either. I also need to work out roughly how the panels will sit on the page – how many I’ll need, and how they run together in relation to the text. It’s really important to get this to a satisfying level now. The further down the line you realise panel-to-panel or page-to-page pacing isn’t working, the more work you’ll need to redo.

At this point in the process I’d often find myself stuck trying to lay out a page. A realisation I quickly came to was that if I was having trouble visualising the page, then there was likely something wrong at the script level. I’d often find that this was the best way to spot a flaw in an argument or a point where I was repeating myself – in trying to draw it all you quickly realise where your words are failing to do their best work.

In all it took two months to thumbnail the book. It felt like a mountain of work, but it was hugely satisfying to see it come together. Words becoming pictures, the book becomes more real in my mind. I can see all the places where I made decisions I wasn’t sure would work. All the places where I struggled to get things right. And now with pictures in place (rough ones that now need fully realised) I can see how it all works, how those decisions were the right ones. It’s a good feeling.